Fairfield’s Philip Eliasoph Celebrates

Painter Robert Vickrey

By: Alistair Highet

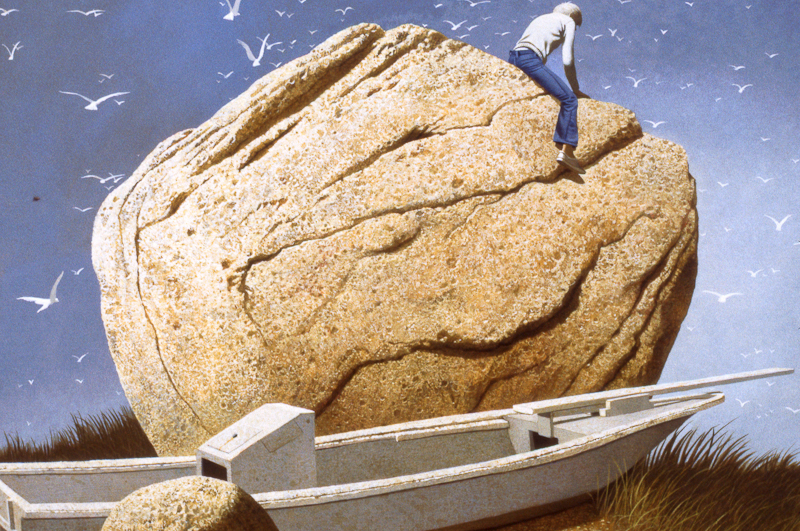

Vickrey painting Admiral Benbow, 1979 Egg tempera on Geso panel, private collection. Photo courtesy Hudson Hills Press.

Robert Vickrey has been one of America’s preeminent realist painters since 1952 when, barely out of the Yale University School of Art, his painting Labyrinth – depicting a nun caught in a bleak labyrinth of corridors – was selected for the Whitney Annual Exhibition. In subsequent years, his paintings, praised for their presentation of the “mysterious in the apparently commonplace,” would be chosen for the Whitney exhibit on eight more occasions, and he would be described by New York Times critic John Canaday as “most surely the world’s most proficient craftsman in egg tempera painting.”

Not that Vickrey would always be in critical favor. While his work is in the collections of 80 leading museums, and the 78 covers that he painted for Time magazine between 1957 and 1968 of public figures like Nikita Khrushchev remain iconic images of the Cold War era, Vickrey has followed a personal vision that has not always been in step with the times. He is dedicated to pictorial representation and a repetition of symbolic themes that have led him to be described as a surrealist, a magic realist, or dismissed as a mere illustrator. During the 1950s and early 1960s, when Abstract Expressionism was the fashion, Vickrey and other realists were pushed to the margins. By the time photo-realism emerged in the 1970s, older realists like Vickrey had already fallen off the critical radar screen.

More than a thousand paintings and drawings later, at the age of 83, Vickrey is still painting. On March 23, Fairfield University President Jeffrey P. von Arx, S.J., presented the artist – who lived in Fairfield for many years – with the Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J., Award for Excellence in the Arts. The award coincided with a retrospective exhibit of the artist’s work in the University’s Thomas J. Walsh Art Gallery, and the publication of Robert Vickrey: The Magic of Realism by Dr. Philip Eliasoph, professor of art history in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at Fairfield.

VFr. von Arx presented Robert Vickrey with the Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J., Award.

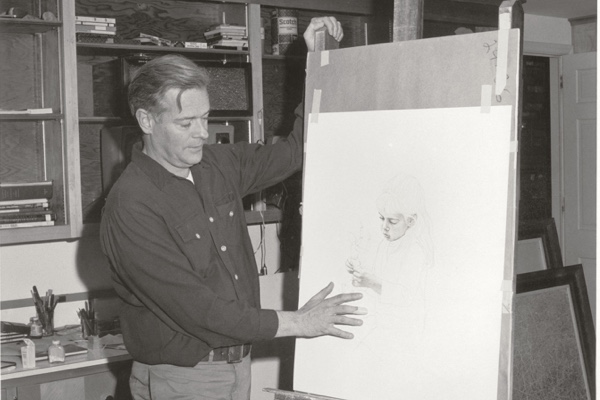

The book, published by Hudson Hills Press, is a comprehensive catalogue of Vickrey’s work. It is also a biographical sketch of an artist who had an unusual childhood – born into wealth, and then suddenly whisked off by his mother to a ranch in Nevada. At age 10, his mother died and Vickrey was sent to a boarding school where he realized his “career was to be an artist.” Dr. Eliasoph has followed Vickrey’s work and been a friend since 1981. When Vickrey was named Artist of the Year by the town of Fairfield in 1982, Dr. Eliasoph curated an exhibition of his work at the University.

Fairfield Now spoke with Dr. Eliasoph about his interest in the artist.

Fairfield Now: How did your interest in American realism develop?

Eliasoph: My formative introduction to the history of art came from my grandmother, who was an American impressionist artist, Paula Eliasoph (1895-1983), and was modestly recognized in the American art world as a protégé of Childe Hassam. So many of the artists of the period were friends of hers. They weren’t mere luminaries; my grandmother told me about these people. At the age of 10, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be a football player or a painter, but I probably lacked the coordination to be either.

As for realism, in terms of my own training as an artist, I came with great humility to realize the inadequacy of my ability. There comes a moment when you need the mastery to be able to put onto the canvas whatever you want to render. My esteem for realist painting came out of a recognition of my own limitations.

Egg tempera on panel, private collection. Photo courtesy Hudson Hills Press

Fairfield Now: How do you respond to criticism of Vickrey’s painting, that it is “illustrative” or “too matter-of-fact” or “lacking in real resonance”?

Eliasoph: Vickrey lives in a zone where there is a cast of characters, where certain themes are repeated – the adolescent lost in a maze, the teenager on the bicycles, the nun who is a symbol for Vickrey of a kind of purity that is unsustainable in our world. I accept that there is Vickrey style, recurrent leitmotifs – that he is exploring a world of light and shadow. One of the reasons that there has been little change in his work over time is that he has refused to pander to what art is supposed to be. Part of what I’m trying to express in the book is that Vickrey, at a time when realist art was considered passé, knew what was going on. He knew that realist painting was out of favor but he said, “Damn the torpedoes. I’m going to stick to what I want to express as an artist.”

Bob Vickrey is himself his own worst critic. He’s going to be 83 in August and he knows that he is still wrestling with the compositional and artistic problems that he first attempted to master in 1949 and 1950.

As for being dismissive of the illustrational and the representational, I am seasoned enough to say that (Johann) Vermeer was considered a minor artist until he was rediscovered in the 19th century, and let’s not forget that masters such as Winslow Homer and Edward Hopper were widely published illustrators in mass market magazines.

Egg tempera on Geso panel, private collection. Photo courtesy Hudson Hills Press..

And let me say something in defense of illustration: What does it say that in December 2001, after the events of 9/11 and the shock of the World Trade Center coming down, that the Guggenheim Museum – the temple of post-modernism – had scheduled a retrospective of Norman Rockwell, and that show had lines around the blocks. It was the biggest blockbuster in memory. Americans came to the Guggenheim for the solace and the emotional balm that Rockwell was able to provide at a time when we were trying to redefine and rediscover ourselves as Americans. America came to see Rockwell illustrate the American experience.

Fairfield Now: How do you think Vickrey will be remembered? Where will he fit in the tradition?

Eliasoph: Vickrey is indelibly written into mid-century American representational painting, regardless of whatever trend or fashionista re-editing is currently being written. I have no doubt that 300 years from now – just as we came to rediscover American painters like John Vanderlyn (1775-1852) and William Sydney Mount (1807-1868) who were also at one time dismissed – that he will be permanently cast into the flow of the current of American realist painting, including what I call painting of the Age of Anxiety, the period between Hiroshima and Vietnam, where we see the themes of loneliness and alienation, the existentialist themes of contemporaries like Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre.